Treating Geographic Atrophy (GA), an advanced form of age-related macular degeneration (AMD)

Treatment options for patients with geographic atrophy (GA) are being developed and clinical trials are currently under way. In this section, we take a closer look at the various treatment approaches under investigation for the treatment of GA. We also delve into the process of drug development and approval for use.

Emerging treatment options for geographic atrophy

While there are not yet any approved medicines to slow or reverse the development of GA, there are several potential medicines currently in development.

The types of new medicines and approaches being investigated generally fall within three categories:1,2

Restoring cell tissue in the eye, either by introducing healthy cells (cell-based therapies) or by repairing damaged tissue (gene therapies)3,4

Cell-based therapy: Uses stem cells, which have the ability to become various different types of cells. In this case, stem cells can be guided into becoming retinal cells and then transplanted into the eye to repair the damage caused by GA.

Gene therapy: Involves replacing a gene that is not working correctly or introducing a new, healthy gene in an attempt to cure a disease. When it comes to GA, gene therapies could be used to repair damaged tissue in the retina, thus reversing the course of the disease.

Addressing overactivation of the complement system in the eye5,6

The complement system is an important part of the immune system, helping to defend the body against injury and pathogens such as bacteria and viruses. Overactivation of the complement system plays a role in a number of diseases, including GA. When the complement system is overactivated this can cause damaging effects such as inflammation and the death of healthy cells. Focusing on addressing overactivation of the complement system may reduce these damaging effects.

Other treatment types, e.g., anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory agents, neuroprotectants7,8

These types of treatments all work to reduce the damage caused by GA or to protect cells from further, ongoing damage.

Antioxidants are molecules that fight free radicals – compounds that can cause harm if their levels become too high in your body.

Anti-inflammatory drugs aim to reduce inflammation in the retina, reducing the damage to cells.

Neuroprotectants may be used to protect cells in the retina and prevent GA from progressing.

What are the steps taken for new medicines to be approved?

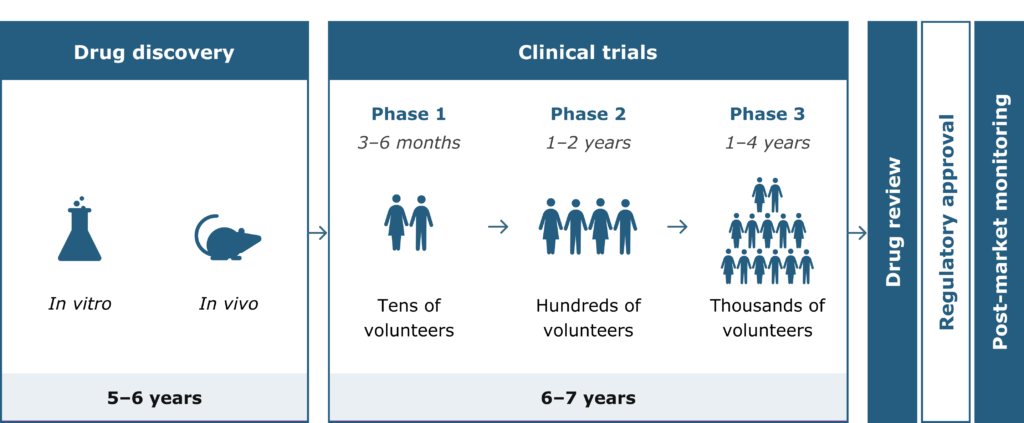

Clinical development, or drug development, refers to the entire process of bringing a new treatment to the market. The path to approval is typically a long journey – around 10 to 15 years, and usually costs hundreds of millions of dollars.9

Drug development stages and timeline9

Possible treatments in development need to be thoroughly tested and approved by government agencies before being available to patients. This is done by carrying out clinical trials: research studies investigating how effective and safe a treatment is in humans.10

Ophthalmology clinical trial overview10

During a clinical trial, researchers divide participants into different groups. Some may receive the new treatment, while others (control group) get either the standard treatment that doctors already use, or a placebo/sham (a fake treatment that has no therapeutic effect).

When possible, clinical trials will be conducted in a double-masked manner, which means that the participants don’t know which group they are in, and neither do the researchers who examine and monitor participants. This helps prevent bias or expectations from affecting the results of the trial.

Depending on the trial, participants may need to do different things, like take pills or receive injections or get eye exams. Participants usually need to come back for follow-up visits over several months or years, so that researchers can see how the treatment works over a long period of time.

Clinical trial phases

Clinical trials in ophthalmology are conducted in four phases. New treatments must successfully pass through each phase of the clinical trial in order to be approved.9,10

Phase 1: Tests the safety of the new treatment in a small group of healthy volunteers and determines whether it is effective and at which dose.

Phase 2: Investigates the treatment in a larger group of people with the target disease to further determine whether it is an effective way to treat or prevent the disease and to evaluate safety.

Phase 3: Compares the new treatment to placebo and/or a current treatment or ‘standard of care’, to establish how effective the drug is in a larger number of patients.

Phase 4: Takes place after the drug has received regulatory approval and has been released onto the market (‘post-approval’ or ‘post-marketing’).

Post-marketing monitoring: Regulatory agencies review any side effects reported by healthcare professionals and patients. If more issues are reported than expected, or are more severe than expected, the regulatory agencies can decide to withdraw the drug from the market.

Joining a clinical trial

By joining a clinical trial, you could be one of the first people to receive a new treatment as an investigational product. You would also be helping to explore potential treatments that could provide future benefit for countless other people with the condition.

Before joining a clinical trial, it’s important to talk to your ophthalmologist or optometrist about whether the trial is right for you. Speak to them about:

- Opportunities to get involved in clinical trials investigating treatments for geographic atrophy

- Information about clinical trials currently ongoing in your area and how to register

Access helpful resources

View the glossary section for further explanation of any unfamiliar terms used throughout this section and across the website.

References:

- Rubner R, et al. Int J Ophthalmol. 2022;15(1):157–166.

- Cabral de Guiemeraes TA, et al. Br J Ophthalmol. 2022;106(3):297–304.

- Singh MS, et al. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2020;75:100779.

- Khan H, et al. Expert Rev Ophthalmol. 2022;17(6):371–374.

- Kim BJ, et al. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2021;83:100936.

- Boyer DS, et al. Retina. 2017;37(5):819–835.

- Scholl HPN, et al. Ophthalmic Res. 2021;64(6):888–902.

- Nebbioso M, et al. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(7):1693.

- Corr P, Williams D. The pathway from idea to regulatory approval: examples for drug development. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2009.

- National Eye Institute. 2021. Learn about clinical trials. Available at: https://www.nei.nih.gov/research/clinical-trials/learn-about-clinical-trials (accessed May 2023).

EU-GA-2300002 June 2023